Hellenism – Reviving the Religion of the Olympians

Stand on the steps of a ruined temple in Greece and listen—the marble may be silent, but the air is alive with echoes. Once, these altars blazed with fire, priests poured libations to the gods, and citizens gathered in festivals that bound the mortal and the divine. The Olympians—Zeus, Athena, Apollo, Artemis, and their kin—were not myths but presences, woven into every breath of life. Though centuries of empire and church sought to bury them, their names endured in story, song, and stone. Now, in the modern world, a movement rises: Hellenism, the revival of ancient Greek polytheism, reawakening the gods who once ruled Olympus and beyond.

What Is Hellenism?

Hellenism is not simply an antiquarian’s pastime or a romantic nod to statues and myths—it is a living revival of the faith of ancient Greece, reimagined and reawakened for the modern world. At its heart lies the conviction that the Olympians and countless other divine beings—nymphs, daimones, heroes, and spirits of land and sea—are not relics of myth, but living presences still worthy of honor.

The word “Hellenism” carries with it the weight of heritage, but it also reflects the diversity of practice. Some practitioners are reconstructionists, carefully combing through Homeric hymns, inscriptions, archaeological evidence, and accounts of festivals to recreate ritual calendars, sacrifices (adapted symbolically), and modes of worship. They see themselves as continuing the work of the ancient priests who tended temples and kindled sacred fires.

Others take a revivalist or devotional approach, shaping modern practices inspired by the ancients but adapted to present-day life. They may create home shrines where libations of wine are poured each evening, or call to Athena before study, Hermes before travel, or Artemis before venturing into wild places. In this way, Hellenism becomes not a reconstruction of the past, but a dialogue across centuries—the gods meet their devotees in both continuity and innovation.

At its core, Hellenism is about relationship: between mortal and divine, human and cosmos, individual and community. The Olympians are not distant abstractions but powers that infuse the natural world—the storm of Zeus, the wisdom of Athena, the joy of Dionysos, the hearth flame of Hestia. Through prayer, hymn, and offering, practitioners reweave the threads of connection that once held together temples, cities, and lives.

It is not an escape into the past—it is the recognition that the old gods never left.

The Olympian Pantheon

At the center of Hellenism stands the Olympian pantheon, a family of gods whose stories have echoed through millennia.

Zeus: Father of gods and men, wielder of thunder, ruler of justice and cosmic order.

Hera: Queen of heaven, goddess of marriage and sovereignty, protector of sacred oaths.

Athena: Goddess of wisdom, strategy, and craft, patron of the city and defender of reason.

Apollo: God of light, prophecy, music, and healing, whose oracles once spoke from Delphi.

Artemis: Huntress and protector of wild places, guardian of youth and women in childbirth.

Poseidon: Lord of the sea, shaker of earth, bringer of both tempest and bounty.

Demeter: Goddess of agriculture and fertility, giver of grain, bringer of mysteries.

Hades and Persephone: Rulers of the underworld, guardians of death and the cycle of rebirth.

Dionysos: God of ecstasy, wine, and divine madness, whose rites dissolved the boundary between mortal and divine.

Yet the Olympians are not the whole of Hellenic faith. River spirits, nymphs, daimones, and ancestral heroes all played roles in the religious life of the Greeks, and many are honored today.

Rituals of the Polis and the Hearth

Ancient Greek religion was both public and private, and Hellenism revives both dimensions.

Household Worship: Every home once had its hearth, sacred to Hestia, where daily offerings were made of food, drink, and flame. Modern practitioners often create home altars—placing candles, statues, or images of the gods, and making small offerings of bread, honey, wine, or incense.

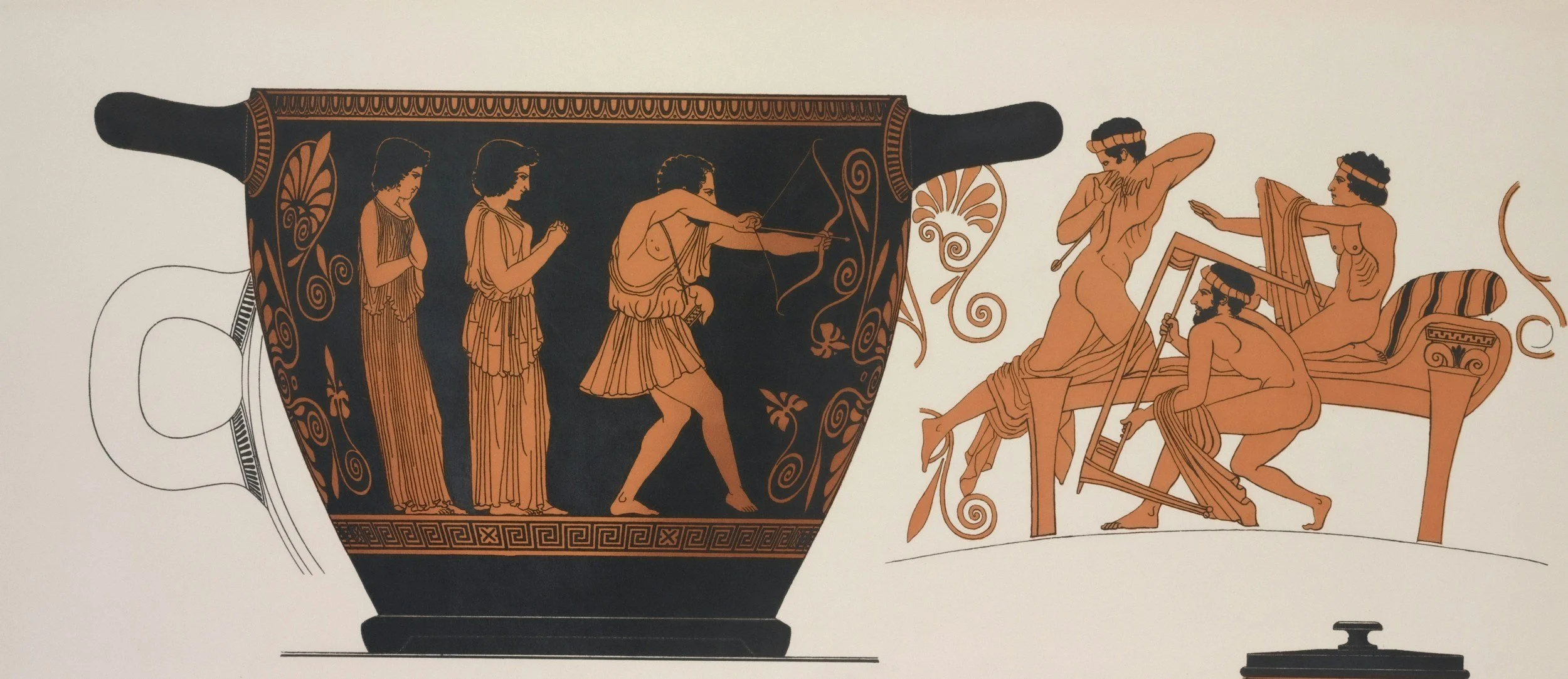

Public Rituals: Ancient city-states hosted grand festivals that honored the gods with sacrifice, music, and drama. Modern Hellenists adapt these festivals, sometimes celebrating the Panathenaia for Athena, or Dionysian rites with music and dance. Animal sacrifice, once central, is now replaced with symbolic offerings such as fruits, grains, or crafted substitutes, reflecting the same spirit without literal bloodshed.

Libations and Hymns: Central to worship are libations—wine, oil, or water poured in honor of the gods—and hymns, many drawn from Homeric and Orphic traditions. These prayers call to the gods in their ancient epithets, reaffirming bonds that span centuries.

Living by Ma’at’s Greek Sister: Eusebeia and Arete

The ancient Egyptians spoke of ma’at—truth, justice, and the balance of the universe—as the principle guiding both gods and humans. The Greeks had no single word to match it, but they lived by ideals just as profound: eusebeia and arete.

Eusebeia is piety—not in the narrow sense of ritual correctness, but in the full-bodied sense of reverence for the gods, the ancestors, and the sacred order of the cosmos. To live with eusebeia is to recognize the divine in daily life: to honor hospitality (xenia), to fulfill oaths, to treat the stranger with dignity, to pour a libation before a meal. It is a quality of right relationship, not only with the Olympians but with one’s community and the unseen spirits that surround human life.

Arete means excellence—the pursuit of living up to one’s highest potential. To the Greeks, excellence was not merely about personal achievement but about aligning one’s gifts with divine purpose. A warrior displayed arete in courage, a philosopher in reason, a craftsman in skill, a mother in devotion. To live with arete is to become a vessel of one’s daimon—the spark of divine essence within—manifesting the best of what one is meant to be.

Together, eusebeia and arete form the ethical backbone of Hellenism. They remind practitioners that honoring the gods is not just a matter of ritual, but of character. To light incense for Athena but neglect wisdom is hollow. To call on Zeus but ignore justice is hypocrisy. The gods ask for offerings, yes—but also for lives lived in harmony with their domains.

In a modern revival, these values still guide. Eusebeia may mean living with reverence for the sacred in a world obsessed with the profane. Arete may mean striving for excellence not as competition, but as a way of honoring the gifts the gods placed in each soul. Together, they ensure that Hellenism is not a religion of empty gestures but of embodied devotion, where ethics and worship are two faces of the same coin.

Shadows and Survival

The gods of Greece were never truly dead—only forced into silence. When Christianity rose to prominence in the Roman Empire, the Olympians were recast as demons, their temples dismantled, their sacred groves cut down. Statues of Zeus were toppled, altars to Athena abandoned, and the flame of Hestia’s hearth was extinguished. Yet even in suppression, the gods lingered like shadows. Their names whispered on the tongues of poets, their myths preserved by scholars who half-condemned, half-adored them, their images carved into stone that refused to crumble.

Through the Middle Ages, the Olympians lived on in disguise. They became allegories in the writings of philosophers, archetypes in Christian moral tales, and embodiments of the human condition in Renaissance art. Painters brushed Athena’s wisdom back into frescoes, sculptors carved Aphrodite’s beauty into marble once more, and playwrights resurrected Dionysos in drunken, ecstatic revelry on stage. The gods wore masks, but their essence endured.

In folk traditions, too, their presence never wholly vanished. Shepherds still muttered prayers to Pan in the highlands, sailors still offered a coin or a libation to the sea before embarking—echoes of Poseidon’s domain carried forward as custom. In every thunderstorm, Zeus’s voice still rumbled; in every harvest, Demeter’s blessing was still felt. The names might have changed, the rituals reduced to shadows, but the rhythms of divine presence persisted in the marrow of culture.

The rediscovery of the classical world in the Enlightenment and Romantic eras brought the Olympians roaring back into consciousness. Poets like Shelley and Byron invoked them, artists filled canvases with their myths, and philosophers dissected their stories not just as tales, but as archetypes of human and divine order. The gods, once buried beneath centuries of dogma, stretched and breathed again through literature, art, and the imagination of Europe.

In the modern age, these shadows crystallized into revival. With the rise of archaeology, the unearthing of temples, and the translation of hymns, practitioners could hear the ancient voices with new clarity. By the late 20th century, communities of devoted Hellenists began to gather openly, pouring libations, celebrating festivals, and invoking the gods not as metaphors but as living beings worthy of worship.

Thus, the survival of Hellenism was not a straight line but a labyrinth—temples to ruins, myths to allegory, shadows to flesh again. The Olympians endured not because they demanded conquest, but because they spoke to something timeless: the awe of the sea, the fire of inspiration, the weight of justice, the intoxication of love. In shadows, they waited. And now, in the open, they rise once more.

The Gods of Olympus Return

To step into Hellenism is to step into a living myth. It is to hear Zeus’s thunder as more than weather, to greet the sunrise as Apollo’s chariot, to pour wine for Dionysos and feel the veil between worlds grow thin. It is to realize that the gods of Greece never died—they waited, patient in marble and memory, for their names to be spoken again.

Hellenism is not about pretending to be ancient Greeks. It is about renewing an ancient covenant, about honoring the gods in ways both old and new, about rekindling the sacred fire of Olympus in a modern world. The altars may be smaller, the festivals adapted, but the devotion is real—and once more, the Olympians walk among us.